On a summer day in 1956, Mary Menner '60 walked to the college from her home on Rundlett Hill. At less than a mile, her trip did not take long—but her journey to attend college was anything but short. Since graduating from high school in St. Louis, Missouri, more than 15 years earlier, she had worked in Washington, D.C., at a Western Union telegraph office, and in Manchester, N.H., at an insurance company. She had delayed college studies long enough. She decided to investigate the possibility of enrolling at Saint Anselm College.

Menner climbed the steps of the Administration Building and was shown to the office of the registrar, Father Stephen Parent, O.S.B. She did not wish to enroll in the nursing program—the department into which women were accepted—but in the college’s liberal arts program. It was an unusual request. Up to that point, the few women who had enrolled as liberal arts students had personal connections with monks or professors.

There were, however, exceptions to the admission practices of Fr. Stephen and the college administration. Mary Menner not only had the academic qualifications for college; she impressed Fr. Stephen with her in-person interview.

“Since you’re a neighbor, we’ll just have to let you in,” Fr. Stephen told her.

The history of women at Saint Anselm is not widely known. Many of their stories have been obscured by the passage of time—but their presence has had a strong, lasting impact on the college.

A Religious Presence

The Benedictine Sisters of St. Walburga’s Convent in Elizabeth, New Jersey were initially invited to New Hampshire by Abbot Hilary Pfraengle, O.S.B., in 1889 to help teach at St. Raphael’s School in Manchester. A group of the Benedictine Sisters was sent to the college seven years later. While working at the college, the Benedictine Sisters had a direct impact on the well-being of students and monks. They cooked meals for both the monks and the students.

Through the pages of early college and student publications, the sisters and their work for the community are well regarded. The Benedictine monks valued the sisters’ presence and work to help the college run smoothly. This value was communicated through the monks’ decision to construct a convent building for the sisters.

When the Benedictine Sisters arrived on campus, they resided in the white house in the front of the college building. This farmhouse, known as the Eaton House, served as their residence until 1915 when the convent was built. The building was eventually named Bradley House after Bishop Denis Bradley. It was constructed on part of the land currently occupied by Goulet Science Center and was moved up the hill to its current position in 1959.

The presence of the Benedictine Sisters lasted approximately 28 years. They include Sr. DeSales Mulvaney (superior), Sr. Frances of Rome Heist, Sr. Adelaide Ryan, Sr. Beatrice Vockel, and Sr. Josepha Walsh. About five local women took vows with this order. Lacking sufficient personnel in their motherhouse, the Benedictine Sisters departed the college in 1924 and returned to New Jersey.

A few of the Benedictine sisters stayed behind for a time to assist with the transition to the Ursuline Sisters of Germany and their work at the college. These sisters from the Ursuline Convent in Duderstadt were called to the college at the request of the director, Fr. Vincent Amberg, O.S.B. ’97. Eleven Ursuline sisters were sent to the college, but remained for a short time. Their motherhouse requested their return in 1926.

With the agreed-upon split from St. Mary’s Abbey, Saint Anselm Priory was elevated to an abbey in 1927. The new Saint Anselm Abbey included monks who were given a choice to remain in Manchester or return to Newark. Among those who stayed was Fr. Bertrand Dolan, O.S.B., who was elected the first abbot of the new community. With a new administration in place, the next chapter of Saint Anselm College was to be written. Chief among the many new things Abbot Bertrand wanted was help again in the college’s kitchen from a religious order.

Following the departure of the Ursuline Sisters, Abbot Bertrand invited the Sisters of Saint Joan of Arc (Soeurs de Sainte-Jeanne d’Arc) from Québec to the college in 1927. Accepting the request was their spiritual leader and founder, Fr. Marie-Clément Staub, A.A. Many of the vocations for this order were from Franco-American families in New England.

The Sisters of St. Joan of Arc arrived on campus on June 16, 1928. The convent was enlarged to accommodate their numbers. From here, the sisters attended to preparing meals and provided the monastery with domestic support, needlework, and prayer. For 60 years, the monks’ habits were sewn by the sisters. (Each cuculla has 73 pleats, for the 73 chapters of the Benedictine Rule.)

Their apostolate was “the spiritual and temporal service of priests.” Because they were semi-cloistered, many students did not really know them. That said, their presence is felt today, seven years after their departure from the college. The granite Cross of Lorraine monument stands in front of Joseph Hall, the former convent building that they lived in from 1955–2008. These sisters were held in high regard by the Benedictine monks and those who understood the meaning of their apostolate.

Our Lady of Grace College

Saint Anselm College was founded to “educate youth, both for the sacred ministry and for the learned professions or for business pursuits.” The course of studies, whether in the preparatory school or the college, was directed towards young men. For nearly 56 years, the college remained primarily a male-only school.

Many people know that the nursing program came before the decision to turn the college coeducational. Before women nurses began attending evening courses in 1949, however, there was, for a brief time, an affiliate program that graduated 10 women in the early 1930s. This program was sponsored by Saint Anselm College in conjunction with the Sisters of Mercy in Manchester. Half of the women graduates were religious. The college was called Our Lady of Grace College. It was an extension of Our Lady of Grace Academy in Manchester, which the Sisters of Mercy operated for many years.

Before Our Lady of Grace College was formed, Our Lady of Grace Academy served as a Catholic high school for young women. The Academy was also important to women returning to complete their high school studies. Many of these adults were registered nurses who pursued nurses’ training before secondary school was a requirement. Recognizing the need to elevate the education of nurses in the state, Mary Durning Davis, R.N., approached the sisters at Our Lady of Grace Academy to request evening and private study for nurses not yet ready to pursue higher education. Our Lady of Grace College filled this need.

The aim of this program was to provide a liberal education to teachers in local parochial schools, many of whom only completed their high school studies. In the first issue of a new student newspaper, The Tower, in 1932, the curriculum of Our Lady of Grace College is discussed as leading to a degree of bachelor of arts “similar in arrangement to the course leading to the same degree at St. Anselm’s, through which the school the young women will receive their diploma. The subjects taught are: Ethics, Psychology, Biology, English, Mathematics, Religion, French, and Latin.” Faculty for these college courses included Abbot Bertrand Dolan, O.S.B., Fr. Placidus Schorn, O.S.B., Fr. Eugene Goellner, O.S.B., and other priests.

The affiliated program was short-lived. By 1934, Mount St. Mary’s College in neighboring Hooksett was chartered and Our Lady of Grace College was no longer necessary.

A “Humane and Christian Calling”

In the late 1940s, Professor Donald Tilden of the chemistry department began teaching students at the School of Nursing at Moore General Hospital in Goffstown. Mary Durning Davis, director of the program at Moore General Hospital, approached the college to provide courses in the sciences and social sciences to their students since they did not have the faculty or facilities to provide for rising educational standards for nurses. The women were to be taught on campus.

In 1950, the Elliot Hospital School of Nursing and the Notre Dame School of Nursing made similar requests for their nursing students. The following year, the college began offering evening classes to meet the educational demands of other local hospitals. Since the next closest school for professional courses was in Boston, the college was strategically positioned to take in these students.

In 1952 the nursing program at Saint Anselm College was established, eventually resulting in a degree program for registered nurses. Bishop Matthew Francis Brady of the Diocese of Manchester was equally interested in this program. The first students were enrolled in 1953.

As this program gained in reputation and popularity, the college needed a separate building to house the Department of Nursing and provide laboratory space. In 1968, Gadbois Hall was completed. At the dedication of this nursing education center, Bishop Ernest Primeau described nursing as “an essentially humane and Christian calling so vital to all of mankind.” Governor John King’s opening remarks highlighted the “tremendous importance of the St. Anselm nursing school to the state and the excellent service it has rendered.”

Although women were now studying and learning on campus, the campus had no accommodations for them. Nursing students were housed at local hospitals and later Memorial Hall, in downtown Manchester. In January 1969, a nursing dormitory was built and dedicated in 1975 as Joan of Arc Hall in honor of the Sisters of St. Joan of Arc and their service to the college. This women’s dormitory was a major change for the college. A 1969 article published in Anselmian News reassured alumni that “Disillusioned old grads will come around, too. After all, the quiet all-male campus that once was St. Anselm’s College has ‘not been the same’ for a long while now. Higher education, at St. Anselm’s and across the nation, is a fast-paced changing world.”

Expanding Roles—on Stage and in Class

Increasingly, students at the college were staging theatrical productions that necessitated shifting from the traditional casting model of the college. In the old model, students played roles for both men and women. Women were not featured in school productions until the 1930s when college students collaborated with local women’s colleges Mount St. Mary’s College (Hooksett) and Rivier College (Nashua). The short-lived collaboration was called the Little Theatre League.

With the founding of the Anselmian Abbey Players in 1949 and the introduction of women to campus in the nursing program, the participation with other women’s college dramatic productions faded. The Abbey Players for a number of years, however, continued to provide male cast members for productions at the local women’s colleges including Notre Dame College (Manchester).

While the faculty was primarily composed of Benedictine monks for many years, there were lay faculty members teaching from the beginning. With the start of nursing courses, there was a clear need to hire experienced faculty to train the nurses. Ruth Bagley, formerly of Elliot Hospital, and Margaret Amsbury of the Veteran’s Administration Hospital in Manchester, were the first women faculty members. In addition to the nursing faculty, other women began teaching at the college. Bagley became the director of the nursing program, a high-level position rare at that time in any Benedictine college or university, especially considering that there were few laymen in positions of leadership at these institutions.

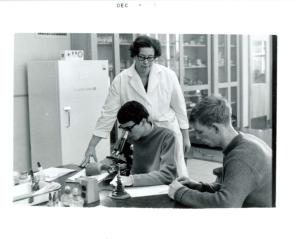

In 1954, the college hired Barbara Stahl and Ann Sullivan in the Department of Biology, with Dr. Stahl teaching until 2004. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, more women were hired for faculty positions. That year, Fanny Delisle, professor of English, became the first woman to serve as president of the Faculty Senate.

With an increased presence in the classroom, women were poised to begin filling administrative positions. In 1971, Norma Creaghe was appointed head librarian and in 1985, Professor Denise Askin of the English department became the first woman in administrative leadership when she was appointed executive vice president. Women also began making an impact on the membership of the Advisory Board of Trustees. Isabelle Gadbois became the first woman appointed to the board in 1970. Women were beginning to be represented throughout the college.

The Co-Ed Question

The decision to go coeducational did not happen overnight. It was first discussed after the 1968 Self-Evaluation Report with recommendations that all programs in liberal arts be open to women. By then, some women had been admitted infrequently for many years, and in the years leading up to the college’s decision to go coed, some women were admitted to the criminal justice program.

Committees were established to address factors that would influence the college, and concluded that it was in the strategic interests of the college to explore becoming coeducational. These committees were comprised of members of the Advisory Board of Trustees, faculty, administration, and students.

Much care and effort went into exploring how the decision to admit women into the liberal arts program would affect the mission of the college. One factor in assessing the issue was how this decision would affect local women’s Catholic colleges. After some study, it was determined that there was little to no direct competition between the offerings of Saint Anselm College and the other schools.

During the Monastic Chapter meeting on November 9, 1973, Abbot Joseph Gerry, O.S.B., advised his confreres to reflect and consider the importance of their proposed decision. He said that they must “reflect on the monastic implications” of going coeducational; to “consider if such a move is in accord with the aims and objectives of the College that is, from an academic and Christian point of view”; to “consider the economic repercussions, both positive, in the sense that it might provide more students, and the negative, in the sense that it will undoubtedly demand certain facilities”; and to “consider the implications of such a move from the point of view of Catholic education in our locale.”

Abbot Joseph stated that women should not be denied the advantage of the unique education in the liberal arts provided by Saint Anselm College. At this meeting, the Monastic Chapter decided in favor of accepting female students in all college programs.

Fr. Brendan Donnelly, O.S.B., president, announced the decision a few days later. Twenty-six women were enrolled for the fall semester of 1974 in the liberal arts program, some as residents and others as commuters (though there was still no dormitory space dedicated to them). Some of those admitted were housed in the nursing dormitory. The college later expanded on-campus housing, starting with the renovation of the Studio in 1975. The Studio soon was renamed Raphael Hall after Fr. Raphael Pfisterer, O.S.B.

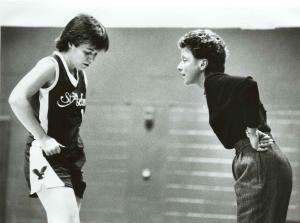

Other aspects of college life changed, as well. In 1976, it was announced that there would be intercollegiate teams in women’s tennis, volleyball, and basketball. Nancy Sommers, the coordinator of women’s athletics (mainly of intramurals), coached the volleyball team. Alan Davis, coach of the men’s hockey and tennis teams, coached women’s tennis. Donna Guimont coached the women’s basketball team. The first intercollegiate contest for women’s athletics was the tennis team’s match against New England College (which they lost). Women’s basketball, however, went on to a 9 and 1 season where they won the Southern New Hampshire Women’s Intercollegiate Basketball Conference championship, beating Notre Dame College.

An Unequivocal Success

Saint Anselm was the last all-male Catholic college in New England, but with the 1974 decision, it was the first American Benedictine college to go coed. The effect on enrollment was almost immediate and exceeded expectations for admissions. Enrollment in September 1975 for full-time students was 484 women and 1,012 men. In 1978, there were 922 men and 670 women. In a relatively short period of time, the college was enrolling and graduating more women than men, a fact that remains to this day.

The first commencement for the class admitted for the liberal arts program was Commencement 1977. The highest grade point average in the class was earned by Margaret Mary Comiskey. In 1978, Mary Rose Donnelly ’78 earned a perfect 4.0 grade point average, the first student since 1944 to accomplish this academic feat. By 1979, women were elected president and vice president of the Student Government Association. All around, the decision to make the college a coeducational institution was met with general excitement and approval. It was an unequivocal success.

Women such as Mary Menner and others who pursued their college degrees at a primarily men’s college were at the forefront of a movement. Certainly, religious women, students, athletes, alumnae, faculty, staff, administrators and Board members transformed the campus during its earlier years—and continue to do so today. Yet as this alumna demonstrates, the college also transformed those pioneering women as individuals. Now 93, Mary Menner states that her walk to the Hilltop on that summer day in 1956 “really changed my whole life and has given me a life that I would never have had if Saint Anselm College had not allowed this young lady to enroll.”