With thanks to Manchester, N.H.–native, Richard Lavalliere, Saint Anselm College is home to a large and significant Franco-American collection of books and archival materials.

In 2008, Richard Lavalliere received an unexpected phone call. The ACA Assurance company in Manchester was in receivership and the State of New Hampshire’s insurance receiver was at the stage of liquidating the assets of the company. A group of local businesspeople were trying to quickly develop a plan to save plaster sculptures the ACA owned. For them, Lavalliere was invited to the meeting as an investor. Little did he know that he was embarking on a journey to save the cultural heritage of his people in New Hampshire and elsewhere.

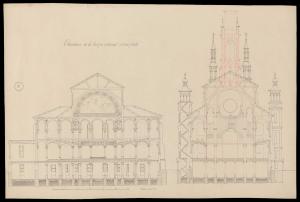

and mural, L’Église St-Antoine de Padoue, Manchester, N.H., 1920, by the architect Jean-Noël Guertin.

At the meeting, the group of 10 or so were focused on purchasing a collection of sculptures by Alfred Laliberté that the ACA acquired indirectly from the Québécois artist in the mid-20th century. While the group assembled in the ACA Assurance’s offices on Elm Street, Lavalliere knew well the ACA’s former building on Concord Street, occupied then by the Franco-American Centre. For some years, his company, Northeastern Sheet Metal, regularly repaired and updated the building for the Centre.

The ACA’s former building had rooms filled with books as well as file cabinets and shelving units containing archival material. Lavalliere asked what was going to happen to the rest of the ACA’s assets—the books, archives, newspapers, artwork, and office furniture. The receiver replied that most of the cultural materials would probably be brought up to Canada to be auctioned off. This did not sit well with Lavalliere. From its headquarters in Manchester, the ACA collected material from individuals and families of French-Canadian descent and the organizations that served them. To Lavalliere, this is where the materials needed to stay.

French-Canadians to Franco-Americans

The Association Canado-Américaine was founded in 1896 as a fraternal benefits society. The ACA provided insurance to French-Canadian immigrants throughout New England. A new country involved many challenges—moving from rural communities to cities surrounded by people speaking English and working in industrial mills managed by people detached from the working conditions and the cultural context of the workforce. For civil and ecclesiastical French-Canadian élites, the move from Québec was loaded with a potential to have the core values of family, the Catholic faith, and more importantly— the French language corrupted.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, nearly a million French Canadians came to the United States, primarily to New England and New York State and others venturing through Ontario to the Midwest. There were migrant workers and people looking to settle in a land that while foreign, had opportunity not present in Québec. The impetus was strong for families to stay together and in some instances almost entire villages moved to New England cities. This also meant importing traditions and establishing a network of institutions to maintain a form of unity between the two relatively close but disparate worlds.

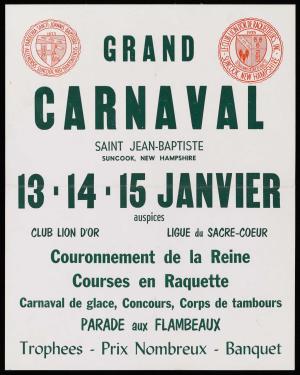

The first French-language newspaper published by French Canadians in New England was Le Patriote canadien (1839–1840) in Burlington, Vt. (it included bilingual stories). Over time, there came to be more than 400 newspapers and periodicals published in New England and New York State. There were newspapers in cities large and small, from Springfield, Mass., to Lewiston, Maine, from Waterbury, Conn., to Plattsburgh, N.Y., from Suncook, N.H., to St. Albans, Vt. La Sentinelle (1924– 1928), a newspaper from Woonsocket, R.I., was founded to protest, among other things, an Irish American bishop’s plans for funding schools that would consign French to a foreign language. While now largely forgotten, the conflict resulted in excommunication for some and reprimands for others.

For its part, the ACA supported cultural and church activities recognizable to both recent immigrants and naturalized citizens. While it sold insurance to Franco-American families like Lavalliere’s, the ACA’s fraternal division sponsored community events and celebrations such as the city’s annual St-Jean-Baptiste feast day parade. The ACA also acquired a significant book collection and later archival materials from individuals and organizations across the U.S. and Canada. With these materials, the society’s ambitions were lofty, its aim was extensive, and its scope was wide.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the French-Canadian élites sought to define themselves as grandchildren of France and children of Québec with the appellation Franco-American. Most families, however, referred to themselves as Canadiens (‘French Canadians’). Even though to established non-French Canadian people it seemed as though there was a continuous flow of people arriving in New England towns from Québec, the French Canadians formed what has been called a large but ‘quiet’ or ‘invisible’ presence. These immigrants were loyal to their heritage as well as to their new country. This is the world in which Lavalliere’s family lived and one that was changing.

Both sides of Lavalliere’s family are French Canadian and his first language is French. He grew up on Manchester’s West Side called le Petit Canada (‘Little Canada’), a few blocks from Ste-Marie Church, not far from Notre Dame Hospital (now Catholic Medical Center) and St. Mary’s Bank (the first credit union in the U.S.). Though it was not the only place in the city where French Canadians settled, it has retained a relatively strong association in some form or another to the French fact in Manchester. One is now less likely to overhear French spoken on those streets than find the echoes of the language in signage or engraved in buildings.

For some in the community, the French language was central to their identity and something to guard at all costs. For others, practical considerations informed their decision-making about this subject in a country with an anglophone majority.

On his first day of classes at Ste- Marie School, Lavalliere came home at lunch bothered by something. He told his mother, “I’m not going back to that school. I don’t know what they are talking about.” Beginning with the earliest Franco-American parochial schools, classes were conducted half day in French and half day in English. Lavalliere did not know any English. His parents, like many, made the decision to begin speaking English in their home to accommodate their children’s academic and social growth.

Families in similar circumstances would likely have heard the expression from some clergy Qui perd sa langue, perd sa foi (‘he who loses his language, loses his faith’). Reflecting on this way of thinking, Msgr. Wilfrid Paradis ’43 said that “saving the language by using religion was a debasement of the faith.” Regardless of one’s position, the bilingual abilities and even the unique French dialect they spoke had few advocates on the outside. External forces were pushing the community to adapt to a different reality. Some gave up speaking French for English, while others navigated their new surroundings with both their mother tongue and a second language.

There are many photographs of Franco-American life in Manchester taken by Ulric Bourgeois, who came to the city around 1900 with an interest in photography. His rural Québec village included both French and English speakers. He established a photography department and a studio at a department store in the city to sell photographic supplies and to photograph individuals and families. Eventually he set up his own studio and furthered his artistic interests by photographing the rural landscape of Québec. His bilingual abilities provided him a pathway to develop his business and artistic pursuits. He was still connected to his heritage.

Around the time the ACA Assurance was going out of business, the Library of Congress adopted the term Franco- Americans to describe permanent residents in the U.S. with French- Canadian birth or ancestry. This is useful since it provides a standardized way to classify and describe content in libraries and archives worldwide. Franco- American had been primarily used for materials describing relations between France and the U.S. In popular culture, it was the name of a processed food brand with no culinary roots in the Franco-American community.

Finding a New Home

After discussions in 2008 with the insurance receiver, Lavalliere had a month or so to accomplish the relatively impossible—negotiate with the receiver on the purchase prices of the statues, library, archives, other artwork, and office equipment; organize investors into limited liability companies for the Laliberté sculptures and the library and archives; insure, move, and store it all—at the same time operating his business. In total, there were 11 investors for the Laliberté sculptures but only three for the library and archives. Lavalliere was the major investor and was now responsible for moving it all.

There were two semi-trailers worth of materials to move. From the ACA Assurance’s current offices came the sculpture, artwork, and books; from the ACA’s former building on Concord Street came more books. “I think I could do a 1 to 2 million dollar sheet metal project with less stress than I had with these books and everything,” Lavalliere says. “It was the most stressful time that I ever had.” His family and many of his employees spent an entire Saturday moving materials from the ACA Assurance’s offices to a new climate controlled storage building at his company. (The archives would remain in the Concord Street building until 2011.)

Now that Lavalliere had saved the materials, he was required to wait a period of time before donating them. Naturally, he questioned his decision. “In the beginning I thought I had really lost it because nobody else was interested.” For Lavalliere, support started at home with his wife. “Lorraine was a big part of it. This took a lot of pressure off of me to have that support.” But still, it was necessary to commence the search for a permanent home for these collections. This would almost prove to be a greater challenge.

Though Lavalliere approached many academic institutions around New England, some were more interested in a donation other than the collections. Starting to get a little discouraged, he asked himself “what are we going to do with these collections?” After careful consideration, the first institution he approached ultimately said yes. His hope from the beginning was that Saint Anselm College would take the collections. It was in the city and he knew the campus. His younger brother George graduated in 1987. As a young man, Lavalliere worked on roof flashing around the Abbey Church in the mid- 1960s.

The meaning of this sizeable gift, and its impact on the college and surrounding community, is notable. “Mr. Lavalliere’s generous support has not only allowed the college to preserve documents and collections, but also preserve the culture and history of the Franco-American community,” says President Joseph A. Favazza, Ph.D. “We are so thankful that his vision and our archival expertise have come together to make this possible.”

The Collections

According to Lavalliere, even though he was funding all the miscellaneous costs including insurance, moving, storage, etc., the pressure started to ease up when he knew he had a home for the collections. Agreements were drawn up. For taking the Québécois artist Laliberté sculptures, the college would provide space on campus for the Franco- American Centre. The college would now be the permanent home for the Franco- American collections and the Geisel Library would receive compact shelving carriages for storing the collections.

The library materials were the first to arrive. Thousands of French language books from Canada, the United States, and France were sorted by staff and selected for the collections by Robert B. Perreault ’72 the ACA’s former librarian/ archivist and current native speaker in the college’s Modern Languages and Literatures department. (Perreault wrote about the book collection in the Fall 2009 issue of Portraits.)

The book collection was named the ACA-Lambert Franco-American Collection in honor of both the ACA and Adélard Lambert, a folklorist and bibliophile who sold his book collection to the ACA in 1918. Books in the collection include well-known authors such as Jack Kerouac, Grace Metalious (née DeRepentigny), David Plante, and E. Annie Proulx whose Franco- American heritage is not widely known. Interestingly, about 27 percent of the more than 4,000 books now in this collection are scarce (that is, held by fewer than 10 libraries worldwide) and almost 120 books are unique (there are no other copies listed in any library). In cataloging these books, the library has made them all discoverable by researchers worldwide.

For three months in early 2011, more than 600 boxes of archival materials were packed up from the Concord Street building and delivered to the college. The Franco-American Archives include unique materials in a variety of formats such as photographs, papers, audio and videocassettes, film, microfilm, and architectural drawings. Current work involves processing, conservation work, and digitization. Students are assisting with project tasks to maintain the collections as well as using the collections for coursework.

Across the archival collection, one can find many examples of the impact made by this immigrant group in the materials collected by the ACA as well as recent acquisitions by the college.

In keeping with its mission to advocate for Franco-Americans and support fraternal activities, the ACA in cooperation with United Cable Company of NH produced a weekly French-language television program called Bonjour! that ran from 1987 through 2000. This magazine format show included segments highlighting the contributions of Franco Americans to artistic, social, cultural, political, and religious life in New England and the United States. In addition, the program documented community events and featured a number of prominent guests including Canadian Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and Québécois singer Céline Dion. Bonjour! was primarily recorded in the studio with some on- location segments. This local origination programming was widely distributed

in New England, New York, Louisiana, Texas, and the Canadian provinces of Québec, Ontario, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. Of the over 500 episodes that were created, the college has digitized a large portion and is currently preparing transcripts to make them more accessible online.

Some collections have been fortuitously collected. Weeks before his death in 1977, local architect Jean-Nöel Guertin met with Perreault. Perreault recorded an oral history interview and was presented with Guertin’s many architectural drawings of buildings in Manchester and New England. Guertin designed La Caisse Populaire Ste-Marie (St. Mary’s Bank) and redesigned the façade and interior of the ACA building on Concord Street. The current St. Mary’s Bank building reflects elements of his original designs.

The collection of Antonio Prince, a former general treasurer for Rhode Island and a vice president and board member of the ACA, includes family papers of correspondence, photographs, and scrapbooks of his uncle, Rev. W.-Achille Prince, one of the supporters of the Sentinellist cause who was dismissed from his pastorate in Woonsocket.

Acquisitions from families, individuals, and organizations are creating a more comprehensive collection. Perreault has donated his audio recordings from more than 40 years interviewing Franco- Americans working in the arts, culture, church, and elsewhere. Included in the collection are papers of Manchester Franco-American mayors Moïse Verrette, Damase Caron, and Josaphat Benoit. In addition, recent donations include the papers of folklorist and writer Julien Olivier; genealogical materials from Fr. Adrien Longchamps; books and items from Maurice Demers ’66; and a set of religious objects, books and family papers from Fr. Dennis Gingras ’76.

The extent and impact of the collections are significant. “Richard Lavalliere saved the singular and extensive collections that the ACA had gathered over decades,” says Br. Isaac Murphy, O.S.B., executive vice president of the college. “The collections are a unique testament to the Franco- American presence in New England. His initial work was key to bringing the collections to the college. His generous and ongoing support allows the college to continue to grow the collections and to make them available to students, researchers, and all who have an interest in the long-standing Franco-American community in the U.S.”

The Future

Significant social and cultural changes began in the 20th century that proved disruptive to the cohesion of this heritage group. Franco-Americans may still retain family customs, but some are increasingly less likely to practice the faith of their ancestors and many know French only as a foreign language taught at school. They may have anglicized their names or may know little of their families’ origin stories. Institutions supporting Franco- Americans have mostly disappeared or have changed to accommodate the new reality. There are many young people, however, who come to a cultural awakening of sorts. They are interested to discover and share their roots, now relatively easy to do online. This is where our collections can serve another group of researchers.

Lavalliere has continued his generous support of the collections. In 2019 he set up the Lavalliere Fund for Franco-American Culture, a $2 million endowment managed by the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation. Through his generous support, the college is able to actively preserve and provide access to these collections; to acquire new books and archival material; to conserve items through repair and digitization; and to collaborate with local and regional partners in highlighting the impact of the Franco-American experience. The college chose the name Lavalliere Franco-American Collections in honor of his legacy saving the collections.

While the future of the collections is strong, Lavalliere admits that back in 2008 he did have his doubts. “At some point, I thought I really made a mistake. I had to keep going. I was running a business and I have good people working for me, but I put in long hours. I didn’t know what to do. I know better now, but for two years I had these collections in storage and wondered ‘did I waste money and the countless hours looking for a home?’”

When asked how he would characterize his actions in saving the library and archival collections, Lavalliere humbly answers: “All I know is it needed to be done. Some of the collections are just irreplaceable. I’ll probably never use them, but I know scholars will. I’m glad I could do it. I couldn’t see it all destroyed. The ACA collected the material, but

the people in Manchester also donated things to the ACA. It should stay in the city.” And for the material now at Saint Anselm College, he says that “you made my day knowing that I didn’t waste my time. This material’s home is in New Hampshire.”

And while the collections call Saint Anselm home, the understanding is that they truly belong to the community. “Saint Anselm College is not an island unto itself,” says Dr. Favazza. “Service to the wider community is part of our mission, and opening up the Franco-American Collections to members of the community is yet another way the college provides resources to those beyond our campus. It is our hope that more members of the community will make use of the invaluable resources of the collections.”

In addition to preserving and providing access to materials, archives and special collections document provenance and the stories surrounding collections. Richard Lavalliere saved the collections from auction or, worse, from being discarded and chose Saint Anselm College in the city where he grew up to preserve the materials of his cultural heritage. His generosity will ensure that these distinctive items of Franco-Americana will be available to everyone here and beyond.

Keith P. Chevalier is the college’s archivist and head of special collections, the director of the Lavalliere Franco- American Collections, and serves as the chair of the Franco-American Collections Consortium. He would like to acknowledge and thank Robert B. Perreault ’72 who is both a friend and Franco-American mentor. This is dedicated to the memory of Fr. Dennis Gingras ’76 whose love of his Franco- American heritage continues to inspire well after his passing in 2022.

Grant Success

The archival core of collections documenting Franco-Americans resides in five institutions in New England who have joined to form the Franco American Collections Consortium. The five institutions are the University of Maine Orono, University of Maine Fort Kent, University of Southern Maine, Assumption University, and Saint Anselm College.

On behalf of the consortium, the University of Maine has received two substantial National Endowment for the Humanities grants. The first award in 2020 was for the Franco American Digital Archives/Portail franco-américain (https://francoamericandigitalarchives.org), a bilingual collections portal providing culturally conscientious access to Franco-American materials at institutions across North America. For the consortium, ongoing work includes partnering with institutions near and far to add relevant materials to the portal and creating culturally specific metadata with a full range of access points that are meaningful to Franco-Americans and French-Canadian and international francophone scholars.

The second NEH grant, for $350,000, was announced in spring 2023, and will be used for digitizing a variety of materials about the Franco-American way of life in consortium collections. These materials illuminate—in French and English—150 years of struggles and triumphs of Franco-Americans from all over New England. This grant will allow more than 8,000 pages of manuscripts, scrapbooks, and papers in the college’s Franco-American Archives to be digitized and added to the Franco American Digital Archives/Portail franco-américain.

“Partnerships with other institutions is a way to extend our limited resources to accomplish larger goals,” says President Joseph Favazza, Ph.D. “Being part of the Franco American Collections Consortium allows the five member institutions to not only share resources with one another, but make a stronger case to grantors such as the NEH that their funding will be maximized to accomplish meaningful goals. This is why the consortium has been so successful in securing grant funding.”

In the near future, the consortium hopes to secure funding to digitize more than 700,000 pages of French-language newspapers published in New England between the 19th and 20th centuries held in repositories in the U.S. and Canada.

—K.C.

See For Yourself

Visitors to the Lavalliere Franco-American Collections are welcome by appointment. Please call 603-656-6197 or visit Anselm.edu/franco-american for more information and to schedule an appointment.